Designing novel airline networks

How entrepreneurs build new businesses with existing aircraft types

Cover photo source - Emirates Airline.

For those that don’t know, I started my career as a network planner for JetBlue. Airline planning offers a dynamic problem-solving work environment and a source of pure joy for airline nerds. The process of network design is a mix of behavioral economics, statistics, and game theory. We make educated, data-driven guesses at how our customers and competitors will react to our route decisions.

Novel airline networks

I love thinking about novel airline routes, particularly those that put an existing airplane type to work in a new franchise.

Designing an airline network is as much an art as a science. Aircraft are flexible. They can fly in unique geographies and be configured with different cabins. United's Airbus A320s only hold 150 passengers, while Frontier's carry up to 186. This flexibility allows entrepreneurs to craft new business models around the same airplanes.

Here are a few of my favorite disruptive airline franchises:

JetBlue's Mint

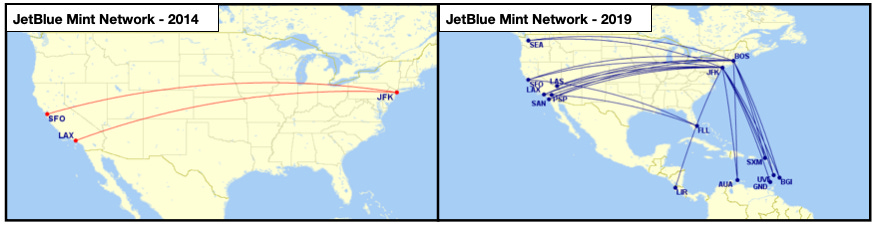

JetBlue launched its Mint business class product in 2014. Its initial routes were New York (JFK) to San Francisco (SFO) and Los Angeles (LAX). Prior, JetBlue had underperformed its competitors on these routes because it didn’t offer a premium product.

The demand for Mint and the sources of that demand surprised both JetBlue and the industry. Mint was designed to cater to high-value leisure customers, not to business travelers. The first surprise was just how many business travelers upgraded on their own dime. The second surprise was how much pressure those same fliers put on their firms to offer Mint. Despite being a budget-premium offering, the product was much better than established business class offerings in the market at the time.

JetBlue has always served markets where it could stimulate traffic. Mint's performance proved that premium markets could be stimulated as well. The stimulatory effect was so strong JetBlue expanded Mint to several new markets that had little existing premium service and no regular lie-flat seating.

JFK originating transcon flying grew, as did Boston and Fort Lauderdale. Then during peak seasons, JetBlue started flying Mint to the Caribbean. Most recently, the company inaugurated Transatlantic service to London.

None of this would've been possible without the Airbus A321. The airplane offered enough floor area for premium and core (economy) cabins and had sufficient range for transcontinental flying. This wasn’t always the case - early versions of the A321 had limited range because it was just a longer, heavier version of the A320. Extra fuel tanks and a light passenger configuration made regular transcon flights possible.

To tackle the Atlantic, Airbus had to extend the A321’s range even further with its LR variant. If it chose, the forthcoming A321XLR would allow JetBlue to fly even further onto the European continent.

Emirates and the A380

Emirates Airline got its start in the mid 1980s. The airline grew modestly at first but by the mid 2000s it seemed unstoppable. The airline's momentum was a critical pillar to the clever development of Dubai.

The Emirate of Dubai, unlike its neighboring emirates, does not have any on-shore oil. Underpinning its economic success is a free trade policy and a focus on tourism.

The success of tourism & business hubs are dependent on air traffic. Dubai’s rise to prominence depended on it's national airline. To help it grow, Emirates developed an ingenious commercial strategy.

Dubai sits within an eight hour flight of two-thirds of the world's population. Rising incomes in much of the developing world meant that more people could also afford to fly. So Emirates built a modern Silk Road, connecting passengers from Europe and Africa to Asia and Oceania.

Most airlines shied from the A380, arguing few markets could support so much capacity. They were generally correct. But Emirates had unique needs for such a beast. A380 meant that Emirates could carry huge passenger loads out of landing slot constrained airports. Pre-pandemic Emirates flew nine daily A380 trips between London and Dubai. Trouble filling the airplane? No problem. Underserved markets in India, China and swaths of Africa are available to stimulate demand.

The A380 had another unique characteristic - its space. Creative product designers imagined palatial premium cabins. The first and business class cabins of the A380 occupy the entire second deck. It is even outfitted with a bar at the rear of the cabin. Best of all, Emirates designed its airport infrastructure around the airplane. The Emirates lounges at Dubai Airport sit levels above the main mezzanine. From there, passengers may board directly onto the second level of the A380. Who wants to see economy passengers anyway?

The A380 defined Emirates' brand. It's now an airline people aspire to fly and clamor to work for. That brand suits the city of Dubai and continues to draw travelers from around the globe. Other airlines in the region are good but nothing beats flying an Emirates A380 to DXB.

British Airways' "banker shuttle"

I first flew the Airbus A318 from Denver to Chicago (Midway). My mother's employer (Frontier Airlines) had bought the airplane. I don't think anyone understood the term 'unit economics' at the airline then. But it was a fun little airplane configured with 120 seats and an abnormally tall tail.

The A318 was designed to be a regional sister to the A320. Short and light, the A318 offered strong hot & high climb performance. Frontier and Avianca were drawn to it as both operated at high altitude airports.

That excellent climb performance was handy for another airline - British Airways. BA equipped its A318s with 32 business class seats and sent them across the pond to New York. The trip originated at London's City Airport, right next to London's banking centre. The service catered to time-sensitive premium passengers, who might've flown Concorde before.

On the westbound leg, the A318 stopped in Shannon, Ireland. The runway at City Airport was too short for a nonstop crossing. BA turned the stop into a positive, as passengers could preclear US customs. The flight then arrived domestically in the United States.

BA's "banker shuttle" as it became known is more novel than transformative. The other two network examples were about building on the capability of the airplane. BA’s transatlantic A318 service was about creatively making use of the aircraft’s limitations.

Nonetheless, I love the creativity that went into developing the service. BA used an otherwise orphan airplane type to serve a highly premium market. Most airlines don't like the risk of technical stops. BA, though, embraced the nuance to create an awesome experience. Airlines should be willing to take these kinds of risks.

Why it matters

The lesson from these stories is aircraft are flexible and opportune markets nascent. Route planners and entrepreneurs need not think linearly about the potential of markets.

JetBlue recognized that premium leisure markets were highly elastic. Emirates recognized the value of its hub geography for connecting flows. It also saw the vitality of air service to the development of Dubai as a prominent world-class city. British Airways took a regional airplane and turned it into a high-yield machine.

Gordon Bethune was a legendary Continental Airlines CEO. He saved the airline (from itself). Nonetheless, he said of JetBlue, "I don't think JetBlue has a better chance of being profitable than 100 other predecessors with new airplanes, new employees, low fares, all touchy-feely... all of them are losers. Most of these guys are smoking ragweed."

Bethune fell prey to the trap of industry experts. Experts struggle to imagine a different product market fit from their own. But as David Neeleman continues to prove, there are untapped use cases for the same airplanes.

It's time to innovate and we don't need to wait for new airplanes to do it.